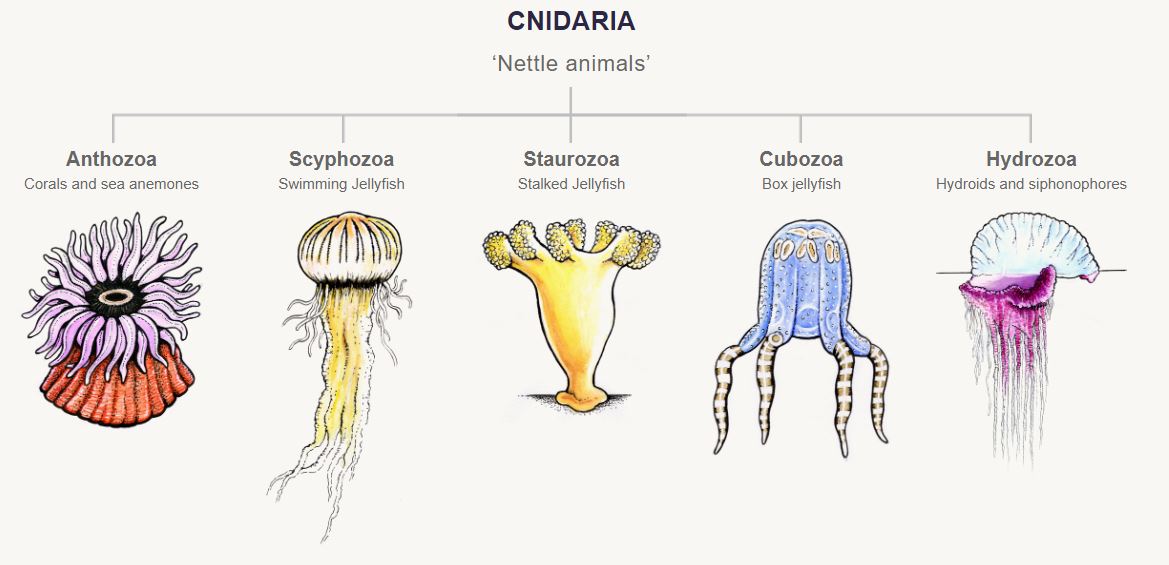

The phylum Cnidaria contains over 11,000 species of aquatic animals, found both in freshwater and marine environments (predominantly the latter), and includes jellyfish, sea anemones, corals, hydroids and some of the smallest marine parasites. Animals belonging to this phylum are more complex than sponges, as complex as ctenophores (or comb jellies), and less complex than bilaterians, which include almost every other animal.

Despite their simplicity, cnidarians have their own unique features, and are very successful organisms when viewed in terms of their diversity and the fact that many are familiar because of their abundance. They were amongst the earliest forms of multicellular life to evolve on Earth, having arisen at least 650 million years ago.

All have a simple structure. Their bodies can be visualized as being sac-like, consisting of the mesoglea, a non-living jelly-like substance, sandwiched between two cell layers, an outer ‘skin’ (i.e., the ectoderm), and an inner lining to the gut (i.e., the endoderm). The center of the body is taken up by a cavity that serves as the gut, with the mouth being the only entrance, as there is no anus. There are no specialized organs for respiration or excretion.

Their most obvious unique feature is the possession of highly specialized stinging cells – called nematocysts or cnidocytes, or even cnidoblasts. These cnidocytes vary in shape and function, but can be described as an explosive cell containing a coiled thread-like sting – the cnidocyst or cnida – that can be rapidly discharged in attack, to capture prey, or defense against predators. In some species, the cnidocytes can also be used as anchors ! The stings penetrate the skin of the target and release toxins in its body. For example, the painful effects of a sting from a bluebottle are well known to bathers. Cnidocytes are single-use cells and need to be continuously replaced.

Cnidarians are some of the only animals that can reproduce both sexually and asexually.

Classification