The phylum Echinodermata – from the Ancient greek ekhinos, a hedhehog, and derma, skin – includes starfish, sea urchins, brittle stars, sea cucumbers and crinoids (or feather stars). With about 7,600 living species, this is the second largest group of Deuterostomia after the Chordata, and the largest marine-only phylum.

SCROLL DOWN

to discover the wonderful diversity of Echinoderms

Taxonomy & Evolution

Echinoderms belongs to the domain Eukaryota, which includes all unicellular and multicellular organisms whose cells have a membrane-bound nucleus and organelles. Within the kingdom Animalia, they are part of the subphylum Eumetazoa, characterized by an embryo that goes through a gastrula stage and the presence of true germ layers, as well as neurons and muscles, at the embryonic stage.

Informally classify in the group Coelomata (i.e., animals with a coelom or general cavity), Echinoderms belong to the infrakingdom Bilateria, meaning they have a bilaterally symmetrical body plan.

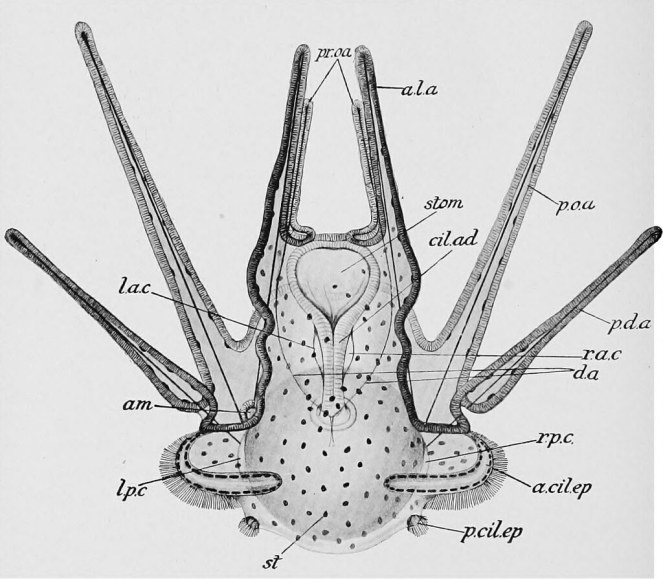

While nearly all bilaterians maintain their bilateral symmetry as adults, Echinoderms are THE exception : they are only bilaterally symmetrical as embryos and larvae, becoming pentaradially symmetrical as adults – they are no front or rear end, but radiate from a central point.

Among the bilaterians, Echinoderms belong to the division Deuterostomia, meaning that the blastopore – the first ‘opening’ to form during embryo development – becomes the anus and not the mouth, and are considered ‘epineurians’, meaning their central nervous system is located dorsally, above the digested tract.

The phylum Echinodermata is further divided into five classes according to several criteria : the presence of the mouth and the anus on the same side of the body, the presence of arms, the type of junction between the arms and the body if the animal has arms or the general shape of the animal itself if there are no arms (e.g., sea urchin).

Anatomy & Physiology

As their name implies, Echinoderms have a calcareous endoskeleton consisting of ossicles, spines and spicules embedded in their skin and connected by a mesh of collagen fibres, although this feature is developed to varying degrees in the different groups.

Echinoderms possess a water vascular system used for locomotion , food and waste transportation, and respiration. The system is made up of canals connecting numerous tube feet. Echinoderms move by alternately contracting muscles that force water into the tube feet, causing them to extend and push against the ground, then relaxing muscles to allow the feet to retract.

Reproduction

Echinoderms reproduce both sexually and asexually, depending on the species of interest.

Sexual Reproduction

Almost all Echinoderms are gonochoric, meaning each individual can either be male or female but not both. Most release eggs and sperm cells into the open water, where fertilization occurs. Such external fertilization is a wasteful affair, and huge quantities of gametes (i.e., eggs and sperm) have to be shed to compensate for this. In some species, the release of sperm and eggs is synchronized, usually with regard to the lunar cycle and other environmental parameters. In other species, individuals may aggregate during the reproductive season to increase the likelihood of successful fertilization.

Echinoderm larvae are attractively transparent, planktonic creatures, and pass through several stages of development. When fully-developed, larvae settle on the seabed to undergo metamorphosis : the left side of the larvae develops into the oral surface – where the mouth is – of the juvenile, while the right side becomes the aboral surface. It is at this stage that the pentaradial symmetry develops.